Thailand will be holding a referendum on adopting a new constitution on August 7. A translation of this document is available here. The nation is currently ruled by a military junta, which took power from the elected government in May 2014. If the constitution is adopted, elections will be held in mid-2017 to choose a new civilian government (though that date has been pushed back a fair few times).

The document provides for a bicameral Thai parliament, as has been the norm for the nation’s numerous democratic constitutions. There is a Senate and a House of Representatives. One of the most substantial changes is that the Senate, which was half-elected and half-appointed by the King (I am unclear whether this was to take place on the advice of the government) under the 2007 constitution, and entirely elected under the 1997 one, will now be wholly appointed. This represents a return to pre-1997 practice.

While the Senate only has a delaying role on most legislation, passage at a joint sitting is required for certain ‘organic’ laws, like those on elections, the operation of the Constitutional Court, and the specific method for choosing Senators. This will become especially important in the first term of government, as the first Senate is to be appointed on the advice of the members of the junta.

The House of Representatives is the larger and more powerful of the two houses. As was hinted at by the drafters of the new document, it is to be elected using mixed-member proportional representation, though with closed lists and a remarkably small list tier (150 list/350 constituency).

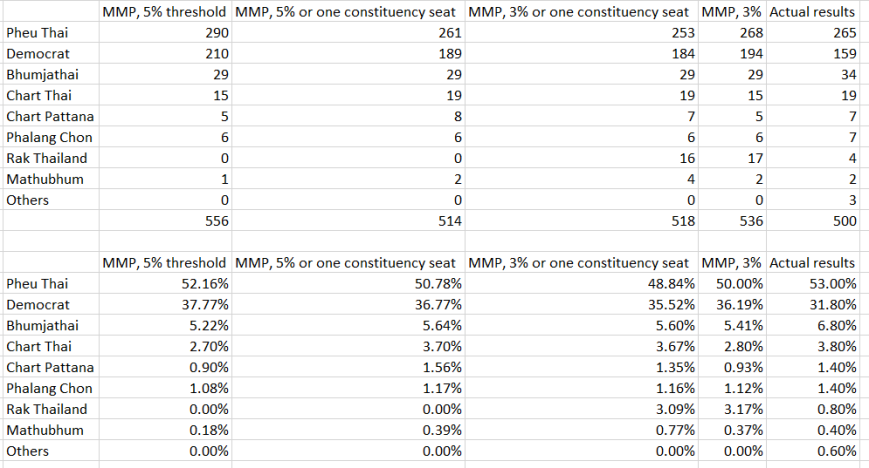

When this proposal was first put about, I did some simulations of what the House would have looked like following the 2011 election had MMP been used. These estimates are based off a smaller list tier (the size of the one used under MMM in 2011). Any increase in the size of the House is due to overhang.

The key loser would be the populist Pheu Thai party, strongly opposed by the coup leaders and the winner would be the Democrat Party, which is considered to have the tacit support of the coup leaders. This would not necessarily be an unfair advantage (given it would give the Democrats a somewhat closer share of seats to their nationwide support), but it would be an advantage nonetheless.

MMP is specifically entrenched in the document. Amendment procedures have also changed; while past documents have allowed a majority of members of the House to make amendments, the new document will require 20% support from opposition parties to make amendments. Needing a super-majority isn’t unusual internationally, but not many constitutions contain quite so many specific electoral provisions as Thailand’s.

What impact increased proportionality will have on Thailand’s democracy is not entirely clear. On one hand, it could require governments to form broader coalitions, which might reduce confrontation in Thai politics and thus less resort to extra-constitutional means. On the other, it could lead to a fragmented House and weak, revolving-door civilian governments, like those that existed before 1997.

It is also worth noting that the elections scheduled for mid-2017, if they take place then, will be held under a law written and approved by the current military-appointed legislature.

Regardless of this constitution, Thailand has clearly got serious problems with military intervention. Previous Constitutions of a similar nature to this one ended in failure. It is unclear whether this one will be any better, though I see it as unlikely.

The Fijian military-imposed constitution also provides for proportional representation, but not not MMP. The military has consistently manipulated the party registration requirements in Fiji to ensure they get the opposition they want and can defeat at elections. Given the obsession of the royalist-military wing of the Thai elite with ‘ethical government’ ( which mysteriously seems to default to government by themselves) it would era surprise if the Thai electoral commission did not become a similar instrument of electoral control.

I have not seen an English translation so I do not know if the king is to have an officially free hand, or merely a de facto free hand, in appointing senators.

LikeLike

Alan, I linked to an English translation in the first paragraph, if you’re interested. It is not wholly clear exactly what sort of influence the King will have on appointment of Senators. There is apparently meant to be a law on how they are chosen, and that will no doubt have more details.

LikeLike

I am aware of the link and when I have time I will read the thing in detail. The Thai king is not a neutral ceremonial figure like Elizabeth II or Emperor Akihito and reference to appointments by royal decree should be read fairly literally.

LikeLike

Could the reason why Thailand is having all these coups due to the fact that the current King has reigned so long?

LikeLike

see this article. Bear in mind that the Thai authorities do monitor blog traffic about the monarchy and have sought to prosecute bloggers visiting Thailand for criticising the monarchy.

LikeLike

The election took place yesterday, and it appears that Pheu Thai has won the most seats (although the fact that 250 military-appointed Senators will vote for Prime Minister will present a challenge if they wish to form government). Results are available (in Thai, but Google Translate deals with it) here.

In relation to the electoral system, my estimates about how the new system would impact the parties (relative to MMM) were partially right and partially wrong. If the 150 list seats were allocated without compensation, Pheu Thai would have gained 35 seats, but the newly-formed pro-military Palang Pracharat party would have picked up 16, and the biggest loser would be the new anti-military Future Forward party, which would have lost 16. The Democrats would have lost four, the centrist (?) Bhumjaithai party would gain three, and other parties would lose eighteen.

LikeLike

Future Forward would have lost 32, sorry.

LikeLike

The results seem to imply this is MMP without a threshold, which is remarkable. Or one can interpret it as evidence that the junta fully intends to utilize its 250 senators as a bloc (as opposed to the relatively more independent minded military-appointed legislators in neighboring Myanmar) to push its own PM candidate, using the excessive party fragmentation as an excuse.

LikeLike

On the new Thai electoral system, I would recommend the recent post by Allen Hicken.

More recent posts at the same blog cover the election results.

LikeLike

In news that will no doubt shock the readers of this blog, Prayuth Chan-o-cha was elected Prime Minister of Thailand with 500 votes to 244 votes for the Future Forward Party’s leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit. He received the votes of every one of the 250 appointed Senators, and the votes of about 250 members of the 500-member House of Representatives.

LikeLike

Well, I never.

Prayuth is said to be in some difficulties with the palace, and his military faction has been almost ignored in recent promotion rounds. He may have managed to position himself in the same place as Thaksin.

LikeLike

Pingback: Thailand electoral system change–again | Fruits and Votes