I wrote about the 2006 election for the Palestinian Legislative Council quite a lot at the time. For instance, as exit poll results were coming in, I warned not to believe their reported lead for Fatah, and indeed they quickly proved inaccurate. Once the results were in, I noted that the magnitude of the Hamas sweep was a product of the electoral system.

In light of recent events, I decided to go back and take an even closer look at the results of that election in January, 2006, which turned out to be not the prelude to a period of calm while Hamas figured out how to use a legislative majority and the near-majority of cabinet seats it received in a unity agreement more than a year afterwards, but a prelude to three major flare-ups of violence between Hamas and Israel. More specifically, I was prompted to go back and look by a remark in Peter Beinart’s article in Haaretz, entitled “Gaza myths and facts: what American Jewish leaders won’t tell you“. The piece itself makes some decent arguments, although I think Beinart is selective in his facts to a degree that is not entirely distinguishable from these apparently monolithic American Jewish leaders he refers to. However, let me stick to the one set of facts I do know something about: the distribution of votes and party strategy in the 2006 election.

Beinart says that one of the reasons Hamas (running under the label, Change and Reform) beat Fatah was “because Fatah carelessly and foolishly ran both its slates in too many parliamentary seats.” Underneath those words he has a link to a You Tube video of a talk by that noted specialist on comparative electoral systems, Bill Clinton (please pardon my snark). On the one hand, I am thrilled that Beinart and Clinton acknowledge that electoral systems and party strategy matter. On the other hand, they actually are perpetuating a myth here. Fatah lost because it had fewer votes, not because it split its vote. Clinton uses the analogy of southern Democrats and their factions in the past when they were dominant in the region. But the analogy is not helpful.*

Fatah did indeed run more than one candidate per district because, well, districts (most of them) elected more than one seat. Hamas did the same, and it did not hurt them. In fact, this was a system in which voters had the possibility to vote for as many candidates as there were seats in their district. Parties could not pool votes, voters could not cumulate nor could they just select a party. (I am not speaking here of the totally separate closed-list PR portion of the electoral system, and from the context I presume neither is Clinton.) A party would win all the seats in a district if it ran a candidate for every seat, and if its voters gave all their votes to candidates of the party. And, of course, if its candidates had the top-M vote totals, where M is the magnitude (number of seats being elected in the district).

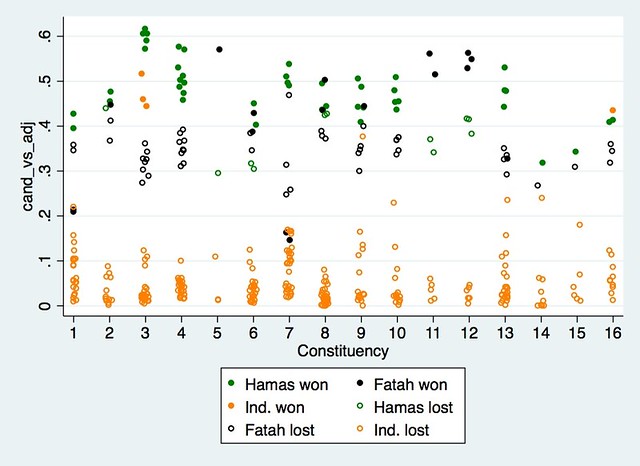

It was actually Hamas that did not always run M candidates. However, the places where it ran fewer were either where some of the seats were set aside for Christians (not surprisingly, Hamas, the name of which is an Arabic acronym for Islamic Resistance Movement, did not contest the Christian seats), or where the seats it did not contest were won by independents. For instance, in Gaza City, eight were elected (M=8). Hamas ran five candidates, Fatah ran eight. Hamas elected all its five, and Fatah elected none. But the reason Fatah did not elect anyone was not that it had too many candidates. The other three seats went to independents. One of these was a Christian, for a set-aside seat. The other two were independents whose vote totals were more than 11,000 votes higher than that of the most popular Fatah candidate. These independents may have been “quiet” Hamas affiliates not bearing the label. One, Jamal Naji El-Koudary, is an academic at the Islamic University of Gaza.

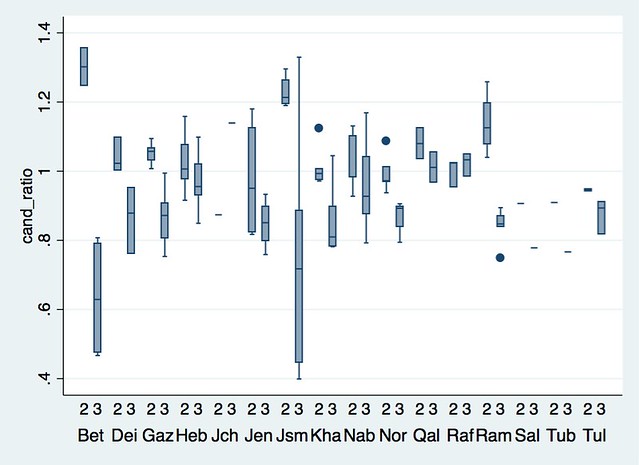

Neither party suffered greatly from any failure of its voters to be willing to cast a full slate by voting for all the party’s candidates running in the district. However, Fatah did suffer a bit more. I calculated the standard deviation of each party’s candidates’ votes in each district. The closer this number is to zero, the closer the candidates were to having identical vote shares:

Hamas, .016.

Fatah, .026.

Not much difference, but enough to make a difference in some places. But this does not mean that Fatah’s running of too many candidates was the reason for winning fewer seats. In this type of electoral system (what I like to call Multiple Non-Transferable Vote, but others call Block Vote), a higher standard deviation can help you win more seats than you otherwise would, in cases where your party overall ranks second. That is, some of the districts where Fatah elected some candidates despite Hamas having one or more candidates with higher vote shares were precisely where it had individual candidates who were more popular than the party as a whole.

For instance in Nablus (M=6), Hamas ran five and Fatah six. The winners were all five Hamas and one Fatah. An independent (Hamas-affiliated?) was the second loser, just behind the second Fatah candidate. The one Fatah candidate who won had 39,106 votes, whereas the party’s next highest vote-earning candidate had 35,397. The five Hamas candidates had from 44,957 to 36,877. The most important point here is that Fatah could not have won more seats simply by running fewer candidates. This is not a single-vote system (like SNTV or like the US primaries Clinton referenced) where running multiple candidates can split your vote. Had Fatah run fewer candidates, its voters would have cast either fewer votes or given the remaining votes to other parties’ candidates, or to independents. It could have won only by running candidates who could beat a Hamas candidate–getting more than the 36,877 won by the district’s sixth-ranked candidate.

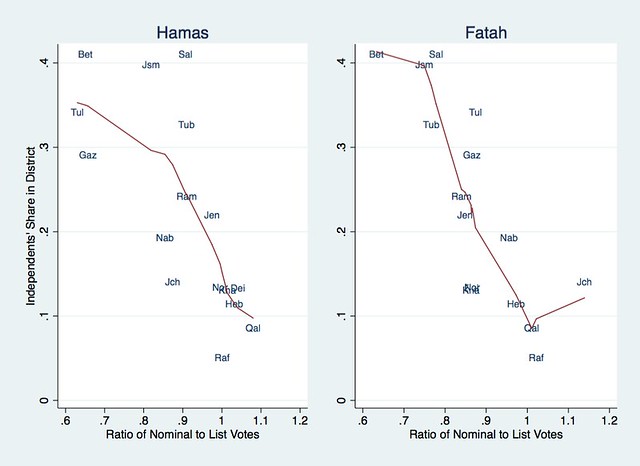

Fatah’s biggest problem was that it just was not as popular. Its collective vote total for candidates was higher than that of Hamas in only six districts out of sixteen. And some of those where it was in second place were the bigger districts, where even a small plurality for Hamas, combined with a low standard deviation of its candidates’ votes, would mean a Hamas sweep. Hamas won a plurality of the candidate votes in Gaza City (M=8, 32.7%-31.7%) Hebron (M=9, 51.1%-35%), Jerusalem (M=6, 33.7%-26.4%), Nablus (M=6, 38.2%-36.5%), among others.

Those vote totals show that Hamas was often well short of a majority. In fact, nationwide, its candidate votes amounted to only 40.8%, but Fatah was well behind (36.6%). That is a lower vote share than in the national list vote, where Hamas won only about 44% to Fatah’s 41%. In fact, I had never summed up the nominal (candidate) votes before. I have always reported the outcome as 56% of seats on 44% of votes, but that is list votes. Given that it was the nominal tier that was the disproportional part of the electoral system, it is actually more accurate to say that Hamas won 56% of seats on not even 41% of votes. It does not change (or reform) the outcome, but it underlines just how disproportional the system was.

A non-proportional electoral system of mostly multi-seat districts sure can turn a small plurality into a big majority. Hamas was more popular, but well short of a majority. The electoral system mattered in a big way, but Fatah’s running multiple candidates was in no sense the reason why Hamas won.

One final observation from the election results: Hamas has controlled the Gaza Strip since its rebellion against the Palestinian Authority in mid-2007, and the Strip was long an important base of operations for Hamas. However, in the election it did not show significantly greater strength in the Gaza Strip, where it won 41.3% of the nominal vote, hardly different from its West Bank support. It did dominate Gaza City’s list vote, however, with 56.7%, which was by far its best showing on the list within in any nominal-tier district. (The list was national, but results are disaggregated by district.) Interestingly, its candidates collectively won only 37.3% in Gaza City. Let’s just say that the personal vote was not how Hamas won, but the disproportionality of the nominal tier more than made up for relatively weak candidates.**

None of this helps resolve the current dreadful crisis, but it does resolve that Peter Beinart, while attempting to counter “myths” with “facts” is perpetrating a myth of his own–as is Bill Clinton–that running too many candidates was what doomed Fatah. That is simply incorrect.

________________

* There was initially a split slate, but party registration was actually re-opened to allow Fatah to present a unified slate for the actual election.

** In most cases, both Hamas and Fatah had higher list than nominal votes. Although there were several small parties running lists that did not have candidates (at least not labelled), there were many independent candidates. Only 4 of them won, and most others were not close to winning. (Their mean ratio of votes to the district’s last winner was .127, and only one had a ratio greater than .66.) They did, however, combine for 20.7% of all nominal votes cast. I can’t rule out that some of them drained votes from Fatah candidates, although that is not Clinton’s and Beinart’s claim. They claim there were too many Fatah candidates.

Data source: Central Elections Commission – Palestine. I used Adam Carr for the district-level nominal votes, because his page was formatted in a way that was more easily transferred to spreadsheet format. I verified that it matched the Commission’s data, and corrected a few examples where it did not. I typed in the list votes per district. I generated various summary statistics and analyses in a Stata file.