If a projection from elespañol (which I found by way of Europe Elects) proves to be essentially accurate, Spain’s general election this Sunday could produce a wee bit of a break with the country’s party-system tradition.

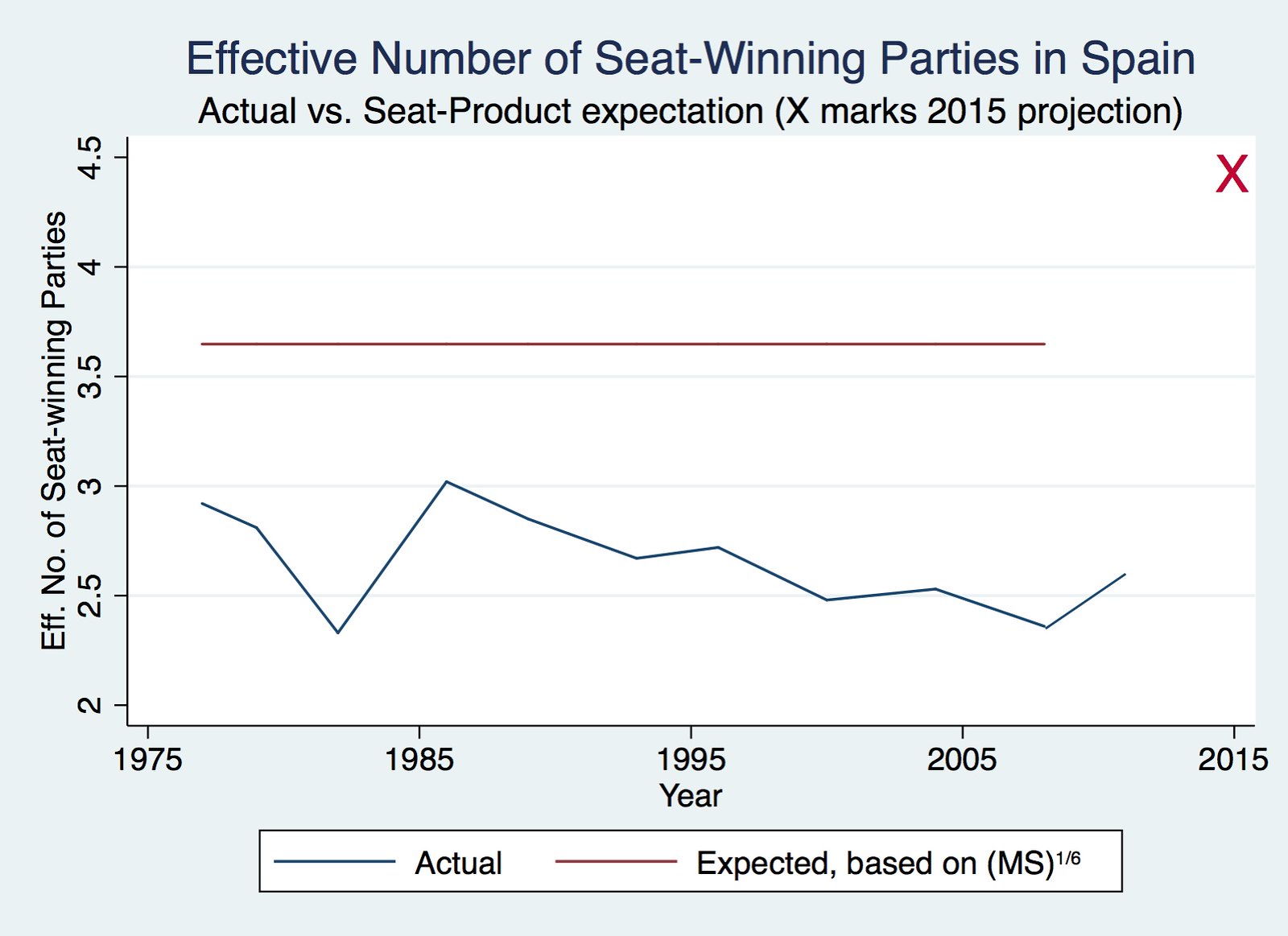

The blue line in the graph tracks the effective number of seat-winning parties in Spanish elections since the return to democracy in 1977. The red line is what we should expect it to be, given Spain’s “moderate” proportional system–where the many districts with small magnitude (number of members elected) has led some scholars to call it an essentially majoritarian, rather than proportional, system. In fact, it has not been uncommon for a single party to win a majority of seats, despite less than half the votes–a rather unusual occurrence under “proportional” rules.

Specifically, the “expected” value is based on Taagepera’s (2007) Seat Product model*, given Spain’s mean district magnitude (around 7) and assembly size (350). The rules have been constant, thus the expected line is straight. Needless to say, Spain has tended to be rather under-fragmented, relative to expectation. We should expect it to have an effective number of seat-winning parties of 3.65, yet the actual value has not even been above 3.0 but once, and has averaged a bit more than 2.5.

The bright red X is what it will be in this election if the projection were to be the actual result. In the trade, we call this an over-correction.

There was a small uptick in 2011, after a long period of steady decline brought on by the dominance of the two main parties, Socialist PSOE and the Popular Party (PP). But the 2011 increase is nothing compared to what could be in store in this election, with the emergence of two new parties, Podemos (on the left of the political spectrum) and Ciudadanos (on the right), which could jointly hold more than a third of the seats.

What this outcome might mean for government formation is an interesting thing to speculate on. I will not offer such speculation, but I am sure some readers have been following the pre-election conversation in Spain about the likely post-election options.

Here are the projected and current seat totals, by party:

| party | seat proj | current |

| Podemos | 62 | 0 |

| IU | 4 | 11 |

| ECR | 8 | 3 |

| PSOE | 79 | 110 |

| Ciudadanos | 57 | 0 |

| DiL | 8 | 10 |

| PP | 119 | 186 |

| EHB | 6 | 7 |

| CC | 1 | 0 |

| UDC | 0 | 6 |

| PNV | 6 | 5 |

| others | 0 | 12 |

| sum | 350 | 350 |

And the effective number of parties by seats (NS) and votes (NV) for each election.

| year | Ns | Nv |

| 1977 | 2.92 | 4.31 |

| 1979 | 2.81 | 4.28 |

| 1982 | 2.33 | 3.19 |

| 1986 | 3.02 | 3.6 |

| 1989 | 2.85 | 4.08 |

| 1993 | 2.67 | 3.53 |

| 1996 | 2.72 | 3.27 |

| 2000 | 2.48 | 3.12 |

| 2004 | 2.53 | 3 |

| 2008 | 2.36 | 2.79 |

| 2011 | 2.6 | 3.34 |

| mean | 2.66 | 3.50 |

| 2015 proj. | 4.42 | 5? |

| revised mean | 2.81 |

Note that the 2015 projection would be so out of line that it actually would raise the full-period mean from 2.66 to 2.81, despite being just one of 12 elections. I put “5?” in the NV cell for 2015, because Li and Shugart (2016; see footnote for link) show that, on average, NV=NS+.6. In Spain, the mean difference has actually tended to be a little higher, at .84. So maybe we will see an effective number of vote-earning parties around 5.3. That would be something–a value we might expect to see in Denmark or Israel (before its fragmentation really took off in the 1990s).

This looks to be one of those rare cases of a really serious shake-up election.

___________

* The Seat Product is district magnitude, M, times assembly size, S. The model states that the effective number of seat-winning parties, Ns=(MS)1/6. Despite its poor accuracy for Spain, it is overall extremely accurate. See Yuhui Li and Matthew S. Shugart, “The Seat Product Model of the effective number of parties: A case for applied political science“, Electoral Studies 41 (March 2016): 23–34.

To many Spaniards in the early days of the transition to democracy back in the mid-to-late 1970s, party fragmentation brought memories of the ill-fated Second Republic of 1931-36 – nearly two dozen parties in Congress, none holding as much as a quarter of the seats – and what it led to, namely a horrific civil war and four decades of Franco’s dictatorship. As such, fragmentation was something to be avoided at all costs., but (as I’ve commented before here), when democracy was gradually re-established and political parties were allowed to operate legally once more, on the first day the government began accepting party registrations there were one-hundred applications. The authorities were so alarmed at what they perceived as the Second Republic all over again that they came up with the PR system “with corrective devices” that remains in place to this day.

Moreover, although far-right parties have not played any significant role in the Spanish electoral arena during the past four decades, in the early days of the transition they retained an outsized influence in the armed forces and the police, where the prevailing (but by no means universal) view was that the emergent democratic regime was an abomination which had to be forcefully terminated at the earliest opportunity. With that in mind, it’s quite likely that a fragmented, Second Republic-style party system resulting in unstable, short-lived governments would have given far-right elements in the military the pretext they needed to step in and abort the transition to democracy long before the 1981 failed coup attempt.

Beyond the constraints of the electoral system and concerns about possible military intervention, other factors played a role in shaping what would become a multi-party system dominated until now by two major parties, with PSOE on the left and AP (the precursor of PP) replacing UCD as the major party on the right in 1982. In the Spanish-speaking world, it is often the case that personalities count as much as (if not more than) ideologies, and as such it is not likely that PSOE would have been as successful as it was early on without the charisma of Felipe González, or UCD without the dynamic leadership of then-Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez. In addition, for the 1977 general election – Spain’s first free vote in over four decades – these two parties received substantial financial assistance from the major parties in what was then West Germany, with SPD lining up behind PSOE, and CDU (as well as F.D.P. to a lesser degree) backing UCD; the Bavarian CSU stood behind Manuel Fraga’s AP, which ran on a hard-right (but not quite far-right) plank nominally committed to democracy yet full of praise for Franco and his legacy; however, AP soon found itself sidelined by the far more moderate UCD – much like the Communist Party was pushed aside by PSOE on the left – and would remain a minor party until UCD imploded in 1981-82.

(Speaking of West Germany, this brings to mind another Spanish election anecdote: in the 1977 election the West German ambassador to Spain found out that his name had been erroneously inserted on the voters’ roll. However, when the ambassador went to the polling station to clarify the mistake, he was told by confounded poll workers that if his name appeared on the list he had a right to vote, and that he should vote…)

At any rate, Spain’s post-Franco party system, centered around two major parties, delivered two long-sought goals at the same time: stable democratic governance and economic prosperity. But the economy tanked more than seven years ago, without having fully recovered yet, and we all know that economic hardship often leads to disenchantment with the status quo and the emergence of new, often extremist political forces. However, I think there’s another factor at work, namely that as the years have passed and Spain’s democracy has matured, the perception that party fragmentation could lead to its downfall has faded away, particularly among the two generations of Spaniards born after 1975, who have no living memory of the Franco regime, much less of the Second Republic and the subsequent civil war.

Moreover, as I noted earlier on, personalities still trump ideologies in Spain. Late polls (whose publication is officially forbidden in Spain but legal in neighboring Andorra) suggest a swing towards the hard-left Podemos, whose leader Pablo Iglesias was judged to have performed well in televised debates with other party leaders earlier this month (while on the other hand PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez was widely perceived as having fared disastrously in the debates). Podemos appears set to match at least the 16.8% share of the vote of its Greek counterpart Syriza in the May 2012 election there (perhaps even arriving second, although that remains highly uncertain at this point). In fact, Mr. Iglesias is so closely identified with his party that wags in Spain often refer to it as “Pablemos.” Personally, Iglesias reminds me quite a bit of Felipe González before 1979, when he and his party embarked on a more moderate course in order to become more electable.

That said, no one appears to have taken the Greek analogy to its logical conclusion, namely that in Greece it took not one, but two elections in 2012 before a stable coalition government could be formed. From that perspective, the outcome of tomorrow’s vote in Spain could prove to be a halfway house, with further changes in the party system lying not too far ahead down the road.

LikeLike

At least Spain has gives more time to form a government, as well as allowing minority government – which then, if I remember correctly, can only be censured constructively. Better chances of stable government there then.

LikeLike

Here are the results out of 350 seats:

People’s Party 123 (-64)

Socialists 90 (-20)

We Can 69 (+68)

Citizens 40 (+40)

Regional -right 15 (- 8)

Regional -left 11 (+ 1)

United Left 2 (- 9)

This is something of a parliamentary mess. From what I can see, the government can still cobble together a majority combining the PP, Citizens, and the more conservative of the Catalonian and Basque regional parties. But the PP has just lost a third of its support, and Citizens is opposed to regionalism, so there is a problem with getting both them and two regional parties on board.

The only alternative is a coalition of the PP and PSOE, similar to what worked so well in Greece.

The left made big gains in the election, but they can’t form a government. It would require the PSOE to co-operate with Podemos, which is trying to replace them, and they would have to somehow convince Citizens to join them.

Assuming the Spanish constitution provides for early elections, another election sometime next year seems most likely.

LikeLike

A few thoughts on yesterday’s election in Spain:

1) The electoral system continues to over-represent the two major parties at the expense of the rest: PP and PSOE won between themselves 60.9% of the seats with a combined 50.7% of the vote, while both Podemos and C’s came up just slightly under-represented (19.7% and 11.4% of the seats with 20.7% and 13.9% of the vote, respectively). Meanwhile, the Catalan, Basque and Canarian nationalist parties’ representation was roughly commensurate to their voting strength, but IU-UP fared badly, with just two seats (0.6%) on a 3.7% share of the vote; that said, the latter brought this outcome upon themselves, as I’ll detail further on. Also, parties that won no seats in Congress accounted for about three percent of the vote; approximately one-half of that total went to either PACMA – the animal rights party – or UPyD, which was completely eclipsed by C’s and lost all its seats.

2) Predictably, the outcome in the smaller sized constituencies was highly skewed towards the major parties: in the eleven constituencies with fewer than four mandates, PP won 17 of 28 seats to PSOE’s nine, while Podemos and C’s won only one each. Podemos did better in the nine four-seat constituencies (with six mandates out of 36), but C’s only won two. No surprises there though, as parties need around twenty percent to win a seat in a four-member district under the D’Hondt rule.

3) Overall, the nationwide center-right parties (PP and C’s) were over-represented, having won 46.6% of the seats with 42.7% of the vote, while the left-wing parties were ever-so-slightly under-represented (46% of the seats with 46.3% of the vote). However, this had a lot to do with IU-UP’s short-sighted decision to compete with Podemos outside Catalonia and Galicia. Combined, Podemos and IU-UP had enough votes to capture an additional fourteen seats, at the expense of PP (seven), C’s (four), PSOE (two) and PNV (one), in the process leaving the left-wing parties just three seats short of a parliamentary majority. That said, PSOE would have still won more seats (88) than Podemos+IU-UP (85), despite polling fewer votes (22% to 24.3%).

4) Despite their wide ideological differences, Podemos and C’s agree on one thing: the existing electoral system, with all its inequities, must be reformed. And speaking of Spain’s electoral law, the ban on publishing poll results five days before the election makes no sense whatsoever in today’s socially networked world, in much the same way as Canada’s recently repealed ban on broadcasting results before the closing of polls. Nevertheless, I thought the “Andorra fruit market” run-around was rather clever – talk about fruits and votes!

5) Podemos also wants constitutional reform, but it seems to me that its “plurinational” concept of Spain – which proved popular in both Catalonia and the Basque Country – is a bit ahead of its time for the rest of the country. That said, further down the road it may prove to be the only sensible way to contain separatist drives in both regions.

6) PM Rajoy let it be known last night that he would try to form a government, and PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez made it very clear as well that Rajoy, as leader of the largest party in Congress, was entitled to attempt so before anybody else. Whether Rajoy will succeed is anybody’s guess. The possibility of yet another election next year is finally being discussed, but I suspect that PSOE – having narrowly dodged a bullet after appearing on the verge of going the way of PASOK in Greece – has little appetite for one, or for that matter a coalition government with PP…which notwithstanding the election result is referred to by Spanish news media as a “grand coalition” (did you see that, Matthew?). I suspect as well that C’s – having seen many potential voters alarmed by Podemos’ rise tactically squeezed back into the PP fold – would rather not have an early election anytime soon, and neither would IU-UP, as it risks being completely obliterated by Podemos, in much the same way as was UPyD by C’s this year.

Under the existing provisions, if King Felipe invites Rajoy to form a government he would need to be backed initially by an absolute majority in Congress. However, if that fails another parliamentary vote can take place a couple days later, and the second time around a simple majority will suffice. With that in mind, one possibility discussed last night on Spain’s TVE was that PSOE might abstain on the second vote and let Rajoy form a minority government. I might add that a similar arrangement has been in place in Sweden for a year now, after the opposition center-right parties reached a budget deal with the Social Democratic-Green minority coalition government, but then again Spain is not Sweden.

7) Finally, while the outcome of yesterday’s election is unprecedented at the national level, similar (and even far more complex) outcomes have been a fairly common occurrence in elections to the autonomous communities’ devolved legislatures over the course of more than three decades. There have been some instances in which the only way out was to hold another election shortly afterwards, but such cases have been the exception rather than the rule.

LikeLike

When writing about the investiture votes, by ‘absolute majority’ do you mean a majority among all MPs, with ‘simple majority’ meaning ‘majority among those voting’?

LikeLike

Here’s the relevant section from the English-language translation of Spain’s 1978 Constitution, available in PDF format here.

Article 99

1. After renewal of the Congress of Deputies, and in other cases provided under the Constitution, the King, after consultation with the representatives appointed by the political groups with Parliamentary representation, and through the Speaker of Congress, shall nominate a candidate for President of the Government.

2. The candidate nominate in accordance with the provisions of the foregoing paragraph shall submit to the Congress of Deputies the political programme of the Government that he intends to form and shall seek the confidence of the Houses.

3. If the Congress of Deputies, by vote of the absolute majority of its members, invests said candidate with its confidence, the King shall appoint him President. If an absolute majority is not obtained, the same proposal shall be submitted for a new vote forty-eight hours after the previous vote, and it shall be considered that confidence has been secured if it passes by a simple majority.

4. If, after this vote, confidence for the investiture has not been obtained, successive proposals shall be voted upon in the manner provided in the foregoing paragraphs.

5. If within two months after the first vote for investiture no candidate has obtained the confidence of Congress, the King shall dissolve Congress and call new elections, following endorsement by the Speaker of Congress.

LikeLike

I also checked out the Standing Orders of the Spanish Congress of Deputies, specifically Section 171, paragraph 5, but it basically repeats the relevant constitutional provision. Unless I’m mistaken, my understanding is that simple majority (“mayoría simple” in Spanish) means a plurality.

LikeLike

Back in 2008, Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero failed to secure the required absolute majority in the initial vote of investiture following the general election, but in a subsequent vote he prevailed by a simple majority of 169-to-158, with 23 abstentions.

Zapatero es investido presidente por mayoría simple.

LikeLike

Shouldn’t that be “està investido”? “Es” implies president [of the government] for life… or is my Spanish wrong here. By comparison, references to “Parliament stands dissolved” is a very rare case where English uses the analogous “is/ stands” distinction.

LikeLike

At lest in Portuguese should be “é investido” and not “está investido” (“investido” is not common in portuguese, at least with these meaning, but the construcion of the phrase should be that) – “investido” is an action that occurs in a specifical moment (the moment of “investidura”), not a continous situation (the prime-minister is “investido” in the moment the parliament accepts him; he is not “investido” during is full term)

LikeLike

What is the difference between majority and plurality when the only two vote options are ‘si’ and ‘no’?

LikeLike

Of course, abstentions are included, but this is a confusing way of denoting types of majority in this context. It’s clearer to say ‘majority of all MPs’ in the first round and ‘majority of those voting in the second.

LikeLike

In English, or legal English, which is not quite the same thing, ‘absolute majority’ has an established meaning: ‘more than half of those who can vote’ and ‘simple majority’ has an equally established meaning: ‘more than half of those who can and do vote’. The meaning is so established that it is used in S128 of the constitution as a threshold for constitutional amendments without further definition.

Thanks Manuel. I suppose an analogy would be saying “XYZ is born 1 January 2016”. It’s a one-off, completed action… doesn’t mean XYZ is immortal…!

Alan’s example shows how translations can affect the law, which in turn affects politics. I recall reading, decades ago, about one or another US State or city whose constitution or charter said that, if one or another committee could not be appointed by consensus, then its members should be “chosen by ballot”. This was not needed for decades and when it was, dispute arose as to whether that meant “by taking a vote” or “by drawing lots”.

I understand that “a majority of the Electors appointed” in the US Twelfth Amendment may not be 100% clear – if, say, Florida had been unable to appoint its 25 Electors in 2000, whether the required majority would have been 270, or only 256, out of the 513 persons who would actually have been seated in the Electoral College.

Various Australian statutes that say “unless the Minister/ Commission/ etc has given consent” are to this day ambiguous about whether this consent can be revoked by the Minister/ Commission/ etc, or if there are no take-backs.

LikeLike

On the es/está distinction with the passive…..”es” is used to refer to an action that is directly taken on a particular occasion or set of occasions, whereas “está” gets used to represent a state of being that is extant over time (yes, it’s the exact opposite of the not-terribly-good permanent-vs.-temporary distinction that most Americans are taught in school to help them make sense of the non-intuitive ser/estar differences).

So to take Tom’s example from above: “Zapatero es investido” refers to an action that someone (in this case the Congreso) has taken to go and invest Zapatero and his government. If one were going to be fully clear about it, the phrase would read “Zapatero es investido por el Congreso” — i.e. Zapatero is invested by the Congress. The alternate “Zapatero está investido” makes no reference to any action whatsoever. It simply means that the current state of affairs is that Zapatero is running a government that has been invested. (It is, I suppose, implied that there must have been some action in the past to bring about this state of affairs, but the phrase “Zapatero está investido” itself says ONLY that there IS a currently-existing state of affairs in which Zapatero happens to be and remain invested.) At any rate, using “está” means that you are omitting any kind of direct reference to an actual action and are instead describing what is simply the way things currently are — it would thus be inappropriate to say “Zapatero está investido por el Congreso” — whereas using “es” means that you are referring to an actual action, in this case the act of investiture.

Or, from a different angle: the government “es investido” at the start of the term when the Congreso casts the vote(s) of investiture, and the government “está investido” throughout the remainder of the term when the existing state of affairs is that the government remains invested.

The explanation of how exactly all of this translates into a past-tense situation, with its further distinctions of preterite vs. imperfect, I will leave to the native speakers. This is, after all, not a website dedicated to linguistics. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Drew. Well, feel free to carry on, as linguistics was almost my major long ago before I stumbled upon political science!

LikeLike

Thank you, Manuel. Excellent detail.

And, yes indeed, a PP+PSOE coalition would not be very “grand”. I also can’t imagine PSOE agreeing to do that, but I can imagine their allowing a PP-led minority government via abstentions.

LikeLike

Regarding Tom’s question above on the Spanish “es” vs. “está”, remember that one becomes “está muerto”, notwithstanding the permanence of the condition. The commonly taught rule for English speakers learning Spanish about when to use which of the verbs for “is” does not always work for specific situations. It is one of those things one just needs to get a feel for to speak the language–and I certainly make mistakes in this verb choice on a disturbingly frequent basis.

LikeLike

In what may (or may not) be a sign of things to come, Socialist Patxi López was elected Speaker of the Spanish Congress of Deputies, following an agreement with PP and C’s. Mr. López – who was head of the Basque Country’s autonomous government from 2009 to 2012 – was backed by PSOE and C’s (130 votes) but opposed by Podemos and IU-UP (71 votes); the remaining 149 deputies from PP and the nationalist parties cast blank or (in one case) void ballots. As part of the agreement, the Bureau of Congress (Mesa del Congreso) – which consists of the Speaker of Congress, four Deputy Speakers and four Secretaries – will have three members from PP and two each from PSOE, Podemos and C’s. Although Bureau members were proportionally allocated among the four major parties, Podemos was very displeased that center-right parties were accorded a majority, and with the fact that PSOE and C’s cut a deal with PP.

Podemos also insists on having four parliamentary groups – one for itself and one each for its Catalan, Galician and Valencian allies; however, PP, PSOE and C’s are adamantly opposed, citing the Standing Orders of Congress, which state that “in no case may a separate parliamentary group be formed by members of the House belonging to the same party. Nor may a separate parliamentary group be formed by members who at the time of the elections belonged to political parties that did not oppose one another before the electorate.”

The Madrid press also commented on the stark contrast between the informal attire of Podemos’ newly-elected deputies and the business suits worn by PP and PSOE parliamentarians – rather reminiscent of the Greens’ entry into the Bundestag back in 1983, I might add.

LikeLike

“Nor may a separate parliamentary group be formed by members who at the time of the elections belonged to political parties that did not oppose one another before the electorate.” By that logic PP shouldn’t be sitting with the Navarrese UPN. But they do, don’t they?

LikeLike

Actually, looking at it again, I’m not sure that last line is consistent with the earlier ones. Groups can’t form out of the same party, but non-opposing parties may not form different groups? Manuel, could you please clarify?

LikeLike

The two UPN parliamentarians elected on a joint ticket with PP in Navarre, along with the Foro Asturias deputy will join the “grupo mixto,” literally the “mixed group” set aside for deputies from parties failing to meet the Standing Orders requirements for establishing their own parliamentary group:

“A parliamentary group may be formed by a minimum of fifteen members. A Parliamentary Group may also be formed by members of one or more political parties which, although not reaching such minimum, have secured no fewer than five seats and at least fifteen per cent of the votes in the constituencies in which they have put up a candidate, or five per cent of the votes cast in the country as a whole.”

The rule preventing the formation of a separate parliamentary group “by members who at the time of the elections belonged to political parties that did not oppose one another before the electorate” applies to parties running in coalition tickets. For example, shortly after the 1986 general election, the Christian Democratic-oriented PDP – which had been part of the Popular Coalition (CP) – broke with AP (the precursor of PP and CP’s senior coalition partner). PDP held twenty-one of CP’s 105 seats in Congress but could not form its own parliamentary group because it hadn’t run opposite CP in the election, and PDP deputies had to join the mixed group.

That said, the Standing Orders provisions governing the configuration of parliamentary groups – which also prevent regional counterparts of a parent party (such as PSC in Catalonia) from having their own parliamentary group – have been interpreted in a flexible (read inconsistent and often self-serving) manner over the years.

LikeLike

While going over the various Spanish news media sites, I’ve noticed what appears to be a recurring problem with every election there, namely that the election night voter turnout rate, which does NOT include Spanish voters residing abroad (the so-called Censo CERA), is erroneously compared to the definitive turnout figure for the preceding election, which of course factors in expatriate voters; ballots cast by Spanish voters abroad will be tallied later this week, and for that reason the Censo CERA is excluded from election day turnout reports. At any rate, the preliminary 73.2% voter turnout rate for yesterday’s election is up 1.5% from the 71.7% turnout in 2011 among voters residing in Spain, but back then less than five percent of expatriate voters took part in the election, bringing down the overall turnout rate to 68.9%.

LikeLike

How relevant is the Senate? The electoral system (limited vote) succeeded in dampening the change, for the 208 directly elected seats, PP won 124 (-12), PSOE 47 (-1), Podemos 9 and C’s 0

http://resultadosgenerales2015.interior.es/senado/#/ES201512-SEN-ES/ES

LikeLike

Not very relevant, except when it comes to constitutional amendments. Put succinctly, in case of a disagreement between the Senate and the Congress of Deputies, the latter has the last word. However, constitutional amendments require a three-fifths supermajority in both houses of the Spanish Cortes; failing that, Congress can override the Senate by a two-thirds supermajority, provided the amendment(s) prevailed by an overall majority in the upper house.

Given the limited powers of the Spanish Senate, elections to that body are something of an afterthought. As Spanish newsweekly Cambio 16 aptly put it back in 1986, the Senate is a chamber “that hasn’t fulfilled its potential,” an assessment which remains valid almost three decades later.

LikeLike

What should be done to reform the Spanish senate? It seems as if it should represent the various regions of Spain. Italy is reforming it’s Senate by making it weaker, and more regional. It will be interesting to see the results of the Constitutional Reform Referendum in 2016. It is always tricky to know what to do with a Senate. You do not want redundancy, nor gridlock. Most countries would be better if there is gridlock between the two chambers, have a joint seating to pass the law an absolute majority, and a national wide refendum to resolve the dispute.

LikeLike

As for the Senate, it seems that the configuration of powers did not leave it with much potential to fulfill.

LikeLike

Indeed. The Spanish Senate is weak, like most of its European counterparts, and that doesn’t give much potential for any meaningful role. Sadly, Italy seems to be moving in the same direction.

Personally I think the best way to give the Senate meaning would be to elect it more proportionally than the lower house and to give it some real power. There are various deadlock-breaking mechanisms that could be used; anything would be an improvement as long as it takes more than a majority in the lower house to override the Senate. I’m not convinced by the idea of representing the regions in the upper house, which leads to regional elections being about the Senate. There are better ways to channel representation of the regions and their interests to Madrid.

LikeLike

Interesting website with investiture votes http://www.historiaelectoral.com/inv.html and tentative make-up of a federal Senate http://www.historiaelectoral.com/senatfederal.html

LikeLike

Interesting indeed – I was visiting that site earlier this week but hadn’t come across either page there at that point.

That said, a Senate reform in the manner proposed there would require a constitutional amendment, which at this juncture seems unlikely to be forthcoming. In fact, any attempt at electoral reform short of a constitutional amendment would have to comply with the provisions set forth in Sections 68 and 69 of the 1978 Constitution:

Section 68

1. The Congress shall consist of a minimum of three hundred and a maximum of four hundred Members, elected by universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage, under the terms to be laid down by the law.

2. The electoral constituency is the province. The cities of Ceuta and Melilla shall be represented by one Member each. The total number of members shall be distributed in accordance with the law, each constituency being allotted a minimum initial representation and the remainder being distributed in proportion to the population.

3. The election in each constituency shall be conducted on the basis of proportional representation.

[…]

Section 69

1. The Senate is the House of territorial representation.

2. In each province, four Senators shall be elected by the voters thereof by universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage, under the terms to be laid down by an organic act.

3. In the insular provinces, each island or group of islands with a Cabildo or insular Council shall be a constituency for the purpose of electing Senators; there shall be three Senators for each of the major islands —Gran Canaria, Mallorca and Tenerife— and one for each of the following islands or groups of islands: Ibiza-Formentera, Menorca, Fuerteventura, Gomera, Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma.

4. The cities of Ceuta and Melilla shall elect two Senators each.

All the same, Spain’s constitutional constraints allow plenty of room for reforming the electoral system. One proposal put forward thirty years ago called for (among other things):

1) Increasing the size of the Congress of Deputies to 400 (the maximum allowed by the Constitution).

2) Reducing the minimum number of seats assigned to the provinces from two to one.

3) Repealing the (largely useless) three percent constituency-level threshold;

4) Allocating constituency seats by the Hare/Largest Remainder method (instead of the D’Hondt rule); and

5) Adopting Hare/Largest Remainder for Senate elections as well, using party lists (closed or otherwise).

In fact, even without changing the existing allocation of seats among provinces, switching from D’Hondt to LR (or for that matter, Sainte-Lagüe) would immediately result in a far more proportionate distribution of Congress seats among parties, relative to their nationwide vote percentages…and for that very reason it would be in all likelihood strongly resisted by both PP and PSOE, since either method would make it far less likely (albeit not 100% impossible) for a single party to win a majority of lower house seats. Moreover, both parties would almost certainly note that for all its shortcomings the existing system has facilitated the formation of stable (and one might add, single-party) governments – that is, until last week’s election…

I don’t know what lies ahead for Spain, but I seriously doubt the party system will revert to the status quo ante for the foreseeable future. Even in a stable, prosperous society as Denmark, the “earthquake” election of 1973 left lasting effects, even though the old major parties managed to more or less hold their ground in subsequent elections. While Podemos and Ciudadanos could conceivably come down to the point their vote percentages no longer translate well into seats – in the case of C’s a three percent drop would suffice for the party to lose forty percent of its seats (or more) – I don’t think either of them is likely to fade away anytime soon, other things being equal. In fact, outside of Andalusia – which remains a Socialist stronghold – Podemos is already Spain’s second largest party, with 21.5% of the vote in the remaining sixteen regions (plus Ceuta and Melilla) to PSOE’s twenty percent; even if Andalusia’s eight provincial capitals – all of them cities with over 100,000 inhabitants, and all but one of them won by PP – are factored in, Podemos still outpolls PSOE by just over a percentage point, although PSOE still won more seats outside Andalusia (68) than Podemos (59).

LikeLike

I should also note that since 1985 Hare/Largest Remainder is used in elections to the Spanish Congress of Deputies, for the allocation of 248 seats among provinces according to their population totals (the remaining 102 being allocated on the basis of two for each one of Spain’s fifty provinces, and one each for Ceuta and Melilla). Thus ironically, while the PR method that favors the larger parties the most (D’Hondt) is used for distributing constituency seats among party lists, the method which favors the less populated provinces the most (LR) is used to apportion seats among constituencies.

LikeLike

This disjunction between the formula for ensuring proportionality among regions/ constituencies, and the formula for ensuring proportionality among party lists, is surprisingly widespread. Some polities – eg Belgium, Spain – use largest remainders among regions but highest averages among lists. The US, by contrast, uses a version of highest average among States (and I recollect at least one State constitution mandates that method – “on the basis of a uniform and progressive ratio” is the legalese used, I believe – for representing counties in its legislature) but when both major parties decide to allocate presidential convention delegates proportionally among competing contenders (the Democrats always, the Republicans sometimes), both use the Hare quota with largest remainder, although the Democrats have a 15% threshold that makes it less favourable than otherwise to lower-polling tickets in the primary.

Horses, for courses, I suppose. Myself I’d advocate highest averages for all allocations that can’t be done by STV (largest remainders are vulnerable to the “Alabama paradox” – 10 seats in a House of 299 but only 9 in a House of 300 – and if there are no preferences then this defect is not compensated for). But D’Hondt in elections among competing party tickets, where there is an should be an incentive for the very minor players to aggregate so they don’t split and waste votes. On the other hand, St-Lague or something similar (equal proportions, or a simplified version with 4/9 or 0.4444… as the qualifying fraction) for allocations among districts (and other fixed groups), since it would be unfair to expect, say, Utah and Nevada to “run a joint ticket” to get one extra seat in the House.

LikeLike

Apportionment (distribution of seats to electoral districts) by a more proportional system (than the allocation of seats to parties) makes sense. The weird things about Spain is that its apportionment doesn’t just guarantee 2 seats for (almost) each province, it gives each province 2 IN ADDITION to its proportional share out of 248; highly reminiscent of the US electoral college (other countries which guarantee a certain minimum number of seats tend to divide up the seats proportionally and only then make adjustments (Brazil, Australia, US House of Representatives)). At least it’s not quite as malapportioned as some of the autonomous community parliaments (For example, each of the Basque provinces has an equal number of seats despite a 1:2:3 ratio in population – interestingly it has not caused much disproportionality in election results).

LikeLike

The UK for centuries had a loading favouring the three Celtic dominions, which were greatly over-represented per capita in the House of Commons compared to England. Scotland, for example, traditionally had around 70-75 seats when per capita it would have had 50-55. I believe this was reduced or even abolished when the mainland Celts got their own devolved parliaments in 1997. In true British constitutional style, of course, no formula was ever spelled out: there was nothing like “one House of Commons member per 50,000 people plus an extra ten for good luck” or whatever. The Representation of the People Act (eg, the 1983 version) simply stipulated the number of seats for each dominion, either as a single number, or as a narrow range (Wales was “34 to 38,” I think, but could be wrong), and England as “not substantially more or fewer than” 518.

Nor was there any attempt to ensure Senate-style equality among the peers for each dominion in the House of Lords. On the contrary, although all English/ Welsh peers got to sit by right (and their number could be increased at any time by royal grant of titles), Scotland and Ireland had a small, fixed number who were elected each parliament by and from their (as it were) peer group.

Macaulay, Burke et al are extremely proud of the fact that the British don’t theorise but rather solve constitutional problems ad hoc, when and as they arise. The Westminster approach is to pick a result that “sounds about right,” and then replace it with a different result if circumstances change, rather than looking for a scalable formula that will automatically produce results that “sound about right” as circumstances change.

LikeLike

The Scottish number was reduced in the first boundary review after devolution. Wales is still overrepresented. Northern Ireland’s representation was actually reduced when it got a devolved administration in 1921 (from 30 to 13), to less per capita representation than the rest of UK. This was increased again in the 80’s when that devolution was abolished.

Under the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011, which will be implemented in the current review, which is to be completed in 2018, there will be a single formula allocating seats to the constituent countries (St. Lague highest averages) as well as a hard maximum deviation rule of 10% from the quota (with exceptions for a few Island constituencies and geographically very large constituencies). Full details: legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2011/1/section/11

LikeLike

As I read Article 69:

1. each province gets 4 senators with a limited number of exceptions that get 3 or 1

2. each autonomous community gets a base of 1 senator plus 1 senator for each million inhabitants

3. provincial senators are elected by the people but autonomous community senators are elected by the legislature

The Spanish senate approaches British levels of constitutional insouciance. Elections must be interesting in the 7 uniprovincial autonomous communities where the province is a community in its own right and some directly elected and some indirectly elected senators represent the same citizens. It is hard to understand why Ceuta and Melilla, with a combined population less than Ibiza’s get 4 provincial senators between them while Ibiza gets 1. Perhaps the authors of this electoral mishmash had a bad experience at a dance party in their youth.

LikeLike

Well, they’ve messed up the bicameralism in more way than one. Even more reminiscent of Canada, where the provinces were grouped into ‘regions’ at first each which got 24 seats: 6 each for the Western provinces, 24 for Quebec and Ontario, 10 each for NB & NS and 4 for PEI. You’d think that when Newfoundland joined in, it would be grouped in with the other Atlantic Provinces… not so, it just arbitrarily got 6. Now NB and NS (0.75 and 0.9 million people, respectively) both have more Senators than Alberta and BC (3.5 and 4.3 million).

The federalists of Spain’s constituent assembly got the autonomy, but not the bicameralism (if they were even trying to get that).

LikeLike

To be fair we don’t know they envisioned every province belonging to an autonomous community. The obvious solution is to reorganise the senate with the autonomous community as the unit of representation.

There is also an obvious solution to my bungled HTML which I hope MSS will be kind enough to fix.

LikeLike

Well, it’s not a hugely important problem, if it is a problem at all. The important thing is that the Senate should 1) have serious powers and 2) be elected in such a way that the government (and preferably also the opposition) is unlikely to have a majority. You could fulfil these criteria while still having the provinces as the territorial basis of representation; for instance, you could make the electoral system MMP, with each province electing a single Senator and another 53 being elected from lists. Whether or not the autonomous regions are equally, equitably or even logically represented doesn’t matter so much.

LikeLike

Surprisingly enough, a reapportionment of Congress seats with an initial minimum of one mandate instead of two and no increase in the size of the lower house would have had practically no overall impact in the allocation of seats among party lists: PP and Podemos would have had a net loss of three seats each, to the benefit of PSOE (+3), DL (+1), IU-UP (+1) and EH Bildu (+1): any gains in proportionality attained from increasing the number of seats in the larger provinces – Barcelona and Madrid would have gained five and six seats, respectively, while Valencia would have picked up two – would have been offset by the reduction of mandates in the smaller provinces, and the ensuing loss of proportionality there: in all, nineteen constituencies would have lost seats, and there would have been ten two-seat constituencies, including Ceuta and Melilla.

On the other hand, a reapportionment with one initial seat per constituency and an increase in the size of Congress to 400 would have resulted in a more proportionate distribution of seats: with an extra fifty seats available, fewer provinces (eight to be precise) would have lost seats. However, PP and PSOE would have remained over-represented, this time along with Podemos, while Ciudadanos would have continued to be slightly under-represented, albeit to a lesser degree. Meanwhile, IU-UP would have ended up with six seats (two from Madrid plus one each in Asturias, Málaga, Seville and Valencia) but even so it would have remained distinctly under-represented, with the highest votes-to-seat ratio of any party in Congress.

Speaking of IU’s misfortunes, El País ran an article yesterday about the party’s desperate attempts to retain its own parliamentary group in Congress, and more to the point the attendant perquisites. If that doesn’t work it’s going to be another nail in the coffin for IU, but again they have no one to blame but themselves for their disastrous showing.

As for the Senate provincial constituencies, I should note that the overall number of elective seats in both houses of the Cortes (initially 557 – El Hierro would not become a separate Senate constituency until 1979) was almost identical to the total number of procuradores in the old Francoist Cortes, and I seriously doubt that was a coincidence. Getting the Francoist legislature to approve the Political Reform Law which paved the way for the restoration of democracy (and in the process vote itself out of existence) was a truly remarkable feat – to this day Spaniards refer to that event as el hara-kiri de las Cortes franquistas – and I’m quite certain that many procuradores were swayed by the prospect of securing a comfy seat in a democratically elected legislature.

Also, the “coffee-for-everyone” concept of devolution was something of a later development. Originally, devolution was envisaged only for the so-called “historic” nationalities (namely Catalonia, the Basque Country and possibly Galicia), with the rest of Spain remaining under more-or-less centralized rule from Madrid. However, back in the early days of the transition, the Socialists – still a hard-left party (not unlike present-day Podemos, but far more willing to compromise than the latter) – pushed for a federal regime in general and specifically for devolution for Andalusia. Consequently, a compromise was worked out, not least because it would also insulate the government from accusations that it was giving preferential treatment to the Catalans and the Basques; however, the latter were less than thrilled with the idea of extending devolution to other regions, as they felt it somehow diminished their claims.

LikeLike

Find it bizarre that Podemos and Ciudadanos got the same number of seats as PP! Can’t they try to form a coalition??

LikeLike

May be the electoral system for the senate may change but I don’t expect a reform of the senate towards the federal model because no-one cares : the centralists don’t want to aknowledge the federal nature of the state by reforming the senate that way while the Basque and Catalan nationalists like the bilateral way of dealing with the center (“we’re special in our own historic right, we’re not like the other autonomous communities”)

May be the conventional wisdom “in federal states, the member-states participate in central decision-making through a federal-stule senate” needs updating with more informal intergovernmental cooperation. I’m thinking of fora like the German Bundesrat or the EU Council of Ministers, but more informal than those two examples, more like the Canadian First Ministers’ conference & Council of the Federation, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and the Austrian Landeshauptleutekonferenz. Also in Belgium there is, besides the Senate (since 2014 reformed towards the federal model), a formal Overlegcomité / Comité de concertation and informal intermninisterial conferences.

LikeLike

I’d say that centralism in Spain, while probably not dead, is largely dormant, at least in its traditional form. None of the major parties call for dissolving the autonomous communities, and while there’s a minor rightist party – Vox – campaigning for the return of centralized rule from Madrid, it fared poorly in last month’s general election. That said, there’s considerable resistance to further devolution (especially on the right), and even proposals from emerging parties (such as the now-moribund UPyD) to take away some powers from the regions and transfer them back to the central government, which are widely perceived (not without reason) as evidence of a “neo-centralist” sentiment of sorts.

LikeLike

OK, ‘centralists’ could have been a wrong chioce of mine, but as I understand it, besides a classical right/left-axis, there’s also an axis pro / contra devolution, with ‘pro’ called nationalist or regionalist. How would I call the other end of that axis, the parties that resist further devolution like PP, C’s, UPyD,…and (less so) PSOE?

LikeLike

The term of choice nowadays for parties like PP, C’s, UPyD and even PSOE is “constitutionalist,” as in defending the existing constitutional order, including devolution as-is. To be certain, the old devolution axis is still very much alive, but its center of gravity has moved well away from centralism.

LikeLike

Sounds frightening, a democracy with parties aligned on an axis ‘constitutionalist versus …’

LikeLike

============================================

Well, “constitutionalist” could have a wider or a narrower meaning.

The wider is that a party is committed to working for peaceful lawful change within the existing constitutional framework, even if it would prefer a different framework (eg on issues such as federal versus unitary, or executive president versus ceremonial president versus ceremonial monarch [the “executive monarch” option has dropped off the menu since 1918 outside Jordan, Swaziland, Thailand and Tonga], or unicameral versus bicameral, or proportional representation versus winner-take-all, or the relative weighting of per-capita apportionment versus per-jurisdiction apportionment, or popularly-elected vs indirectly-elected vs appointive versus hereditary offices.

The narrower meaning is that it is committed to preserving that framework against all attempts to change it, even peacefully and lawfully. Eg, many in the GOP would view themselves as “defending the Constitution” by opposing attempts (if any serious attempts got off the ground) to abolish the Electoral College with a direct election amendment. Most Australian referendum campaigns see the “NO” side appealing to “defend our strong Constitution,” confusing the section 128 alteration procedure with a military coup or the like.

LikeLike

Prime Minister Sanchez has dissolved Parliament and called another election after Catalan separatist parties voted to reject his budget. Polls suggest that in addition to PP, PSOE, Podemos, and C’s, the hard-right Vox party is likely to win about 10% of the vote for the Chamber of Deputies, after the party won 11% of the vote and 12 of 109 seats in last year’s Andalusian regional election.

LikeLike

As it has been discussed here many times, Spain’s “rectified” PR system is well-known for its tendency to skew the distribution of Congress of Deputies seats in favor of the larger nationwide parties. This continued to be the case in the 2015 and 2016 general elections, but at the same time there was a significant change in the way the votes-to-seats distortions manifested themselves. Specifically, in both elections – particularly the latter – the overall distribution of mandates in constituencies with 5-6 or more seats was highly proportional. Meanwhile, disparities in the allocation of seats in constituencies with fewer than 5-6 seats intensified to record levels. In other words, votes-to-seats distortions in Spanish legislative elections, which previously were usually spread across most constituencies outside Madrid and Barcelona (where the large number of seats has always insured highly proportional seat distributions) are now concentrated in the smaller constituencies.

The main reason for this change has been the emergence of two new, mid-sized parties – namely Podemos and C’s – capable of competing seat-wise in constituencies with as little as five seats, and in the case of Podemos/UP in 2015 and 2016, in constituencies with four seats as well. However, both parties have had considerable difficulties winning seats in three-member constituencies because the most proportionate seat outcome in those (or perhaps the least disproportionate), namely a 1-1-1 allocation among the top three parties, requires the third-largest party to win at least 50% + 1 of the votes cast by the party arriving first, which in practice has translated into an effective threshold in the vicinity of 20%. Moreover, the then-smaller C’s struggled to reach effective thresholds of over 15% in four-member constituencies, to the point a one percent decline in 2016 left the party with no seats in districts with fewer than five members, despite polling a double-digit share of the vote in them.

So far, this state of affairs has worked to the advantage of the two major parties, especially PP and particularly so in the three-member districts, which have seen very little seat movement since PP’s landslide victory back in 2011, despite the dramatic changes in Spain’s political landscape in the course of this decade. Even though the emergence of Vox has added a further element of uncertainty – pollsters forecast the far-right party will have a significant showing, although they haven’t agreed on how significant it will be – PP and PSOE are expected to continue to benefit in a disproportionate manner from the allocation of seats in the smaller constituencies (albeit probably as much as in previous elections, particularly in the case of PP). If UP, C’s and Vox poll at least around 12% of the vote each – the average effective threshold for six-member districts in both 2015 and 2016 – the aggregate distribution of seats in districts with at least as many seats should remain fairly proportional. However, votes-to-seats distortions in constituencies with five or fewer members may not only remain substantial, but prove to be crucial in deciding what kind of government emerges from Sunday’s vote, if any at all.

LikeLike